Part One:

"My Amateur

Days"

A Vivid Retrospection of the Days

When a Radio "Bug" Who

Claimed to Extract Mes-

sages From the Ether

Was Declared

Mentally Un-

sound.

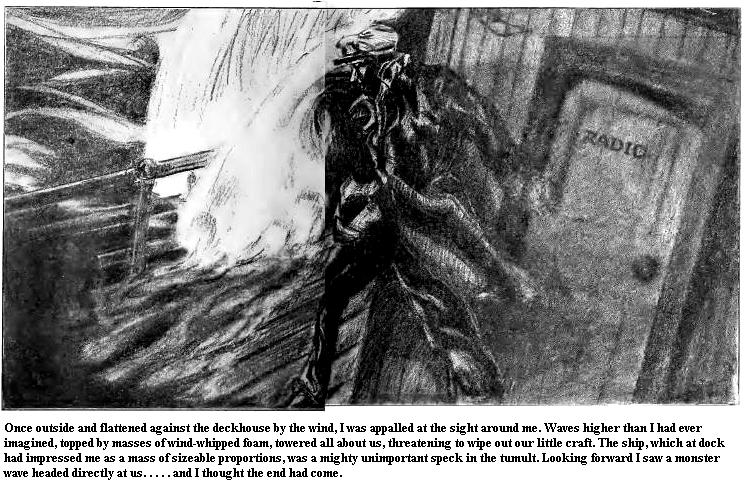

| THIS article is the first of an interesting series by a veteran commercial operator, who describes the facts and thrills of his rise from an awe-inspired experimenter, back in 1907, to a full-fledged radio expert. Don't fail to miss a single installment, you amateurs! |