Approximately 1,500 persons died when the Titanic sank on April 15, 1912, including some of the most prominent persons in the world. During the three days it took until the Carpathia steamed into New York harbor with 711 survivors, there was intense interest in learning the details of the accident, plus who had lived and who had died. Because broadcasting didn't exist at this time, newspapers handled some of the breaking news by posting information on bulletin boards located outside their offices, which quickly drew huge crowds of interested persons.

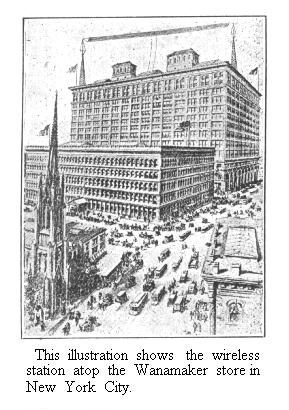

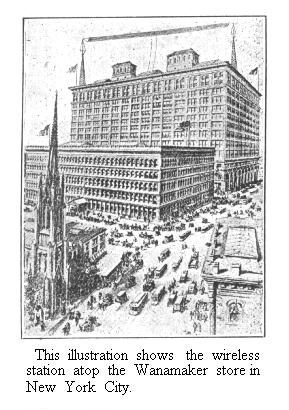

The use of radio for long-distance communication during the disaster created extensive publicity about the tremendous value of a technology that was still very new to most people. When it became known that the Carpathia was transmitting survivor lists, which were being relayed by other stations, many sites which had radio receivers were also mobbed. The receiving sites included the American Marconi station located atop the New York Wanamaker department stores. David Sarnoff, the New York station's manager (and future president of the Radio Corporation of America), produced some of the best known, and unfortunately, most exaggerated accounts of this event. (His stories were generally believed to be factual until 1976, when Carl Dreher's biography, An American Success, began to set the record straight. Kenneth Bilby's 1986 biography, The General, also helped provide a more accurate view of Sarnoff's actual activities).

Sarnoff's progressively more expansive accounts falsely credited himself as being the first person in the United States to hear about the Titanic, and also as the sole source supplying the entire nation with information. Actually, American Marconi merely had an agreement to supply the Hearst Corporation newspapers with information received at the Wanamaker-New York station, and at least three qualified operators were on hand at the station. Contrary to Sarnoff's claim, U.S. President Taft never ordered other stations to shut down to clear the airwaves for Sarnoff's station -- in fact, the only case where President Taft ever became involved was related to charges that Marconi operators had ignored the President's request for information about an aide who had been on the Titanic.

Boston American, April 16, 1912, page 4 (station drawing from the January, 1911 Modern Electrics, page 569):

AMERICAN GETS WIRELESS NEWS IN NEW YORK OFFICE

MARCONI STATION, WANAMAKER STORE, New York, April 16.--The wireless office of the Wanamaker stores at Broadway and Eighth streets, conducted jointly by John Wanamaker and the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, were converted into a branch office of the Hearst Newspapers.

MARCONI STATION, WANAMAKER STORE, New York, April 16.--The wireless office of the Wanamaker stores at Broadway and Eighth streets, conducted jointly by John Wanamaker and the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, were converted into a branch office of the Hearst Newspapers.

"Jack" Binns, the hero of the Republic-Florida disaster, when he shot to the world the wireless "C. Q. D." and saved the lives of over 2,000 passengers and crew, took charge.

The office was directed by David Sarnoff, manager of the station, assisted by J. H. Hughes, an expert Marconi operator. With every bit of energy at their command the men stood by their work and fired scores of messages and caught many concerning the wreck. From all over the coast line and far into the interior, even to Chicago, appeals for news of the disaster were heaped upon the temporary office.

The Wanamaker Marconi office is located on the roof of the famous department store and is one of the most powerful along the Atlantic seaboard. Through all the pandemonium of the wireless conversation and confusion, this station managed to pick up direct communication with Siasconsett, Sagaponack, Cape Cod, Hatteras, Sable Island and many other stations along the coast.

Faint signals were heard from the Olympic, but owing to the terrific confusion and disruption of static conditions, Mr. Hughes was unable to pick up the strands of direct communication. Other New York offices were unable to report any communication at all with the Olympic. Here are some of the wireless messages picked up:

CAPE RACE, Newfoundland, April 15.--The latest advices from the Olympic state she is in the zone of disaster. Olympic confirms that steamship Carpathia reported the position last reported by the Titanic as 41:46 N. and 50:14 West about daybreak.

CAPE RACE, N. F., April 15, 9:55 p. m. Orders to cancel the special train for passengers for Halifax to New York, we are now informed, means that the Carpathia is headed direct for New York.

Bringing in Survivors.

HALIFAX, N. S., April 15.--Orders have been countermanded for the special train to convey the surviving Titanic passengers to New York. It is believed here that the Carpathia, carrying the surviving members of the crew and passengers is trying to make either New York or Boston.

"Radio", by David Sarnoff as told to Mary Margaret McBride, The Saturday Evening Post, August 7, 1926, pages 141-142:

News of the Titanic Disaster

I came back to New York from the ice fields in 1910, and when John Wanamaker decided to equip his New York and Philadelphia stores with radio stations more powerful than any then installed in the commercial field, I applied for the place of operator, because it would leave my evenings free to take a course in engineering at Pratt Institute. So it happened that I was on duty at the Wanamaker station in New York and got the first message from the Olympic, 1400 miles out at sea, that the Titanic had gone down.

I have often been asked what were my emotions at that moment. I doubt if I felt at all during the seventy-two hours after the news came. I gave the information to the press associations and newspapers at once and it was as if bedlam had been let loose. Telephones were whirring, extras were being cried, crowds were gathering around newspaper bulletin boards. The air was as disturbed as the earth. Everybody was trying to get and send messages. Some who owned sets had relatives or friends aboard the Titanic and they made frantic efforts to learn something definite. Finally, President Taft ordered all stations in the vicinity except ours closed down so that we might have no interference in the reception of official news.

Word spread swiftly that a list of survivors were being received at Wanamakers and the station was quickly stormed by the grief-stricken and curious. Eventually a police guard was called out and the curious held back, but some of those most interested in the fate of the doomed ship were allowed in the wireless room. Vincent Astor, whose father, John Jacob Astor, was drowned, and the sons of Isidor Straus were among those who looked over my shoulder as I copied the list of survivors. Straus and his wife went down too.

I remember praying fervently that the names these men were hoping to see would soon come over the keys, but they never did.

Much of the time I sat with the earphones on my head and nothing coming in. It seemed as if the whole anxious world was attached to those phones during the seventy-two hours I crouched tense in that station.

I felt my responsibility keenly, and weary though I was, could not have slept. At the end of my first long tryst with the sea, I was whisked in a taxicab to the old Astor House on lower Broadway and given a Turkish rub. Then I was rushed in another taxicab to Sea Gate, where communication was being kept up with the Carpathia, the vessel which brought in the survivors of the ill-fated Titanic.

Here again I sat for hours--listening. Now we began to get the names of some of those who were known to have gone down. This was worse than the other list had been-- heartbreaking in its finality--a death knell to hope.

I passed the information on to a sorrowing world, and when messages ceased to come in, fell down like a log at my place and slept the clock around.

MARCONI STATION, WANAMAKER STORE, New York, April 16.--The wireless office of the Wanamaker stores at Broadway and Eighth streets, conducted jointly by John Wanamaker and the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, were converted into a branch office of the Hearst Newspapers.

MARCONI STATION, WANAMAKER STORE, New York, April 16.--The wireless office of the Wanamaker stores at Broadway and Eighth streets, conducted jointly by John Wanamaker and the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, were converted into a branch office of the Hearst Newspapers.